Introduction

Energy transition has been a key element in Tunisia’s official discourse for years, aligning with the global context that drives investment in renewable energies and reduces dependence on fossil energies. In this discourse, renewable energies, particularly photovoltaic energy and “green” hydrogen, are presented as the ideal solution that will enable the country to overcome its energy deficit and attract foreign investments, thereby contributing to addressing the economic crisis.

However, these headlines, promoted by the Tunisian state and the “supporting” international institutions in this matter, obscure the fact that these investments further deepen regional disparities and perpetuate the same exploitative mechanisms of the extractive model. These investments come at the expense of citizens in the interior regions, generating profits for investors without delivering genuine developmental or environmental benefits to the country.

An aspect of the injustice of these investments is evident in land exploitation for the construction of solar or wind power plants. In this context, President Kais Saied used the authority of decrees to remove obstacles to the exploitation of public and agricultural lands for these projects. As for the communal and private lands, particularly in the south, where land ownership remains a contentious issue between the authorities and local residents the government has accelerated its efforts by using coercive measures to impose investors’ control over these lands, as is currently happening in the villages of Sagdoud, Chenini, and Douiret.

This approach is not isolated from the European countries’ pursuit to diversify their energy supply sources to achieve their own goals and indicators at the expense of the environmental and economic interests of the Global South, through non-transparent agreements covered by attractive slogans such as energy transition and economic cooperation.

This paper aims to shed light on the challenges related to these projects and to highlight the issues that need to be taken into consideration to ensure that the Tunisia’s energy transition is fair and driven by a national desire to achieve energy self-sufficiency and to guarantee citizens’ right to access energy.

Energetic Transition: “A Misleading Paradigm”

The discourse on “transition” in general represents one of the elements of the internationally dominant global discourse, especially when related to concerning the Global South. “Transition” is often claimed to be an inevitable path to progress and prosperity, taking various forms that are promoted in the literature of international institutions, such as digital or energy transition.

These seemingly attractive or even self-evident terms obscure many critical aspects of these transitions. How are they being carried out, and for whose benefit? Does every transition necessarily lead to a good model? What kind of transition is being promoted by international institutions and their financial and technical arms?

European-centric socio-technical approaches1 dominate studies on “transition”, where it is viewed in this context as “significant technological shifts in the operation of social functions such as transport, communication, housing, and food”2 or as “deep structural changes in systems—such as energy—that involve complex and long-term restructuring of technology, policies, infrastructure, scientific knowledge, and cultural and social practices for sustainable purposes3.”

However, despite some modifications, his theory overlooks important dimensions related to the political economy of transition, such as, power dynamics, interests, and historical and social dimensions. The differences in institutional and social contexts of each country lead to the adoption of different energy transition pathways, influenced by power dynamics, international influences, and the prioritization of political choices—whether to promote renewable energy or focus on inclusive development.

In the context of energy transition, other geographical studies indicate that energy transition embodies pathways with varying spatial and social impacts. Reshaping economic and social activities based on these pathways leads leads to different outcomes depending on social groups and areas,4 which do not benefit equally from the extraction, generation, financing, distribution and consumption of energy5.

Thus, two competing visions/paths for energy transition nature can be distinguished:

- A market-based and extractive-oriented vision, encouraged by international institutions, leads to a liberal model based on privatization. This vision neglects many structural dimensions of transitions, such as power relations and interests. In fact, it justifies the adoption of the neoliberal model of transition, which subordinates all sectors, including vital ones, to the logic of the market and profit. International institutions rely on the use of loans, development financing, and alliances with local forces that benefit financially and politically from this transition, to legitimize and impose this model on Global South countries. Its impact also intersects with the interests of many additional stakeholders: global capital, transnational corporations active in the energy sector, international “development” banks, and local political elites6.

- A comprehensive vision for the energy transition that takes into consideration various social, environmental, and gender-related factors (such as democracy, transparency, colonial legacy, energy and economic dependency, etc.), as well as the interests of different stakeholders, particularly indigenous people, farmers, and women. This proposal is embodied in the principle of a just energy transition, whose characteristics were clearly outlined at the meeting of environmental and labor movements in Amsterdam in 2019, including gender, class, racial, and democratic dimensions7.

Our vision of a just energy transition, and our consideration of its political economy dimensions in the Global South, compels us to view it in the Tunisian context as a component of a global system that perpetuates energy dependency. In this system, international institutions influence Global South countries to adopt an extractive, neoliberal energy model that incorporates renewable energies as one of energy production sources, without bringing any real change in the nature of the extractive system and its disastrous effects on land and people’s lives.

Moreover, our perspective on a just energy transition does not align with the lexicon adopted by neoliberal institutions that appropriated this term to serve their own narrative after embracing it in the preamble of Paris Agreement under the pressure of social, environmental, and labor movements. The use of this term often remains at the level of slogans, merely to cover up the usual policies8, a practice these institutions have consistently applied in all the other areas as well, such as debt, austerity, and subsidies.

Strategies for Energy Transition in Tunisia: What Transition and for Whom?

The energy transition in its core definition —namely, the shift towards energy sources with lower carbon emissions (as defined by the International Renewable Energy Agency, IRENA)—represents a significant challenge for Tunisia amidst social and political changes and increasing energy demand. Currently renewable energies sources, which are proposed as the primary alternative in this energy transition, contribute by only 3% of Tunisia’s energy mix, a very insignificant percentage far from the national goal of reaching 30% by 2030.

The main challenges facing the current energy system in Tunisia include securing energy demands, governing the subsidy system, and the impact of reliance on fuel and gas imports on social aspects and quality of life. However, facing these challenges should be connected to all aspects of a just energy transition and should be particularly directed toward meeting the needs of the Tunisian market, rather than adopting a liberal model that could lead to the privatization of energy sector, environmental harm, and depletion of the country’s natural and water resources.

Historically, Tunisia transitioned from being an energy exporter to a net energy importer since the beginning of the third millennium, due to the increase in demand and the decline of local energy production9. Although Tunisia was an exporter of oil and gas until the 90s, it became an importing country over the past decade. The energy balance (measured by the energy independence ratio) has shifted from a surplus (124% in 1990) to a deficit since 2001 reaching 80% in 201210 and 48% in 202311.

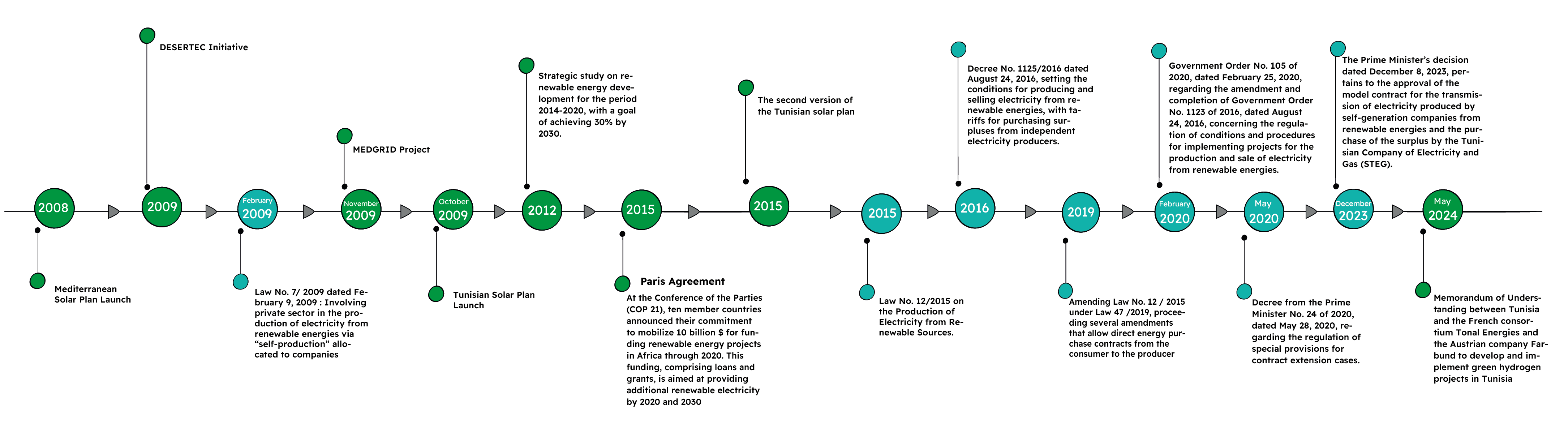

Tunisia’s national energy policy did not undergo a transformation until 2009 only saw a significant shift in 2009 with the launch of the Tunisian Solar Plan, which coincided with and was linked to the Mediterranean Solar Plan launched by the European Union in the same year, in cooperation with the countries of the southern and eastern Mediterranean, as part of the Union for the Mediterranean, to achieve its goals in the field of renewable energy.

Since the launch of the Mediterranean Solar Plan, the National Agency for Energy Management (ANME) has adopted a more “proactive” approach in providing incentives to enhance energy governance and make significant progress in renewable energy and to reduce dependence on conventional energy sources and limit greenhouse gas emissions, or so it is claimed in in every successive national strategy since the launch of the Mediterranean Solar Plan. When it comes to global greenhouse gas emissions, Tunisia’s contribution is a mere 0.07%, which raises questions about the central importance placed on this issue in energy projects undertaken in Tunisia in collaboration with the European Union. Especially considering that this focus has required the mobilization of substantial resources, estimated at approximately 18 billion USD12, to fund investment needs and capacity-building programs.

In this context, the French government launched an initiative in November 2009 to explore the feasibility of transmitting direct current over long distances between solar and wind energy production centers and consumption points across the Mediterranean basin, as part of the MEDGRID project. This initiative aims to establish an integrated network of energy transmission pipelines that connect the northern and southern shores. The MEDGRID project is focused on studying and developing an advanced offshore electrical grid that links North Africa with Europe, thereby facilitating the exchange of renewable energy between the two regions and optimizing the use of solar and wind energy resources in the southern Mediterranean.

It becomes evident that what seems like Tunisian energy policies is a direct outcome of European impositions. Northern countries tailor these policies to align with their commitments and aspirations, often in response to pressures such as those arising from the Russian-Ukrainian war and their dependence on Russian gas.

The European Union, on the one hand, is trying to reduce its dependence on traditional energy sources and achieve its environmental goals, while on the other hand, seeks to secure alternative and sustainable energy sources to address geopolitical fluctuations.

Therefore, the Tunisia’s legislative framework development, related to renewable energies is often shaped by the influence of European partners and their efforts to persuade authorities to adopt the reforms they impose.

The influence on the legislative framework is a key element of the “modus operandi” that underpins the strategies of Northern countries to exploit the resources of the Global South. European lobbying takes many forms to influence the legal and institutional framework, such as facilitating policy dialogues between governmental and private actors or using the guise of technical assistance to develop various national strategies of southern countries. This is evident in the Tunisian case, where the German Technical Cooperation Agency funded most of the studies related to the energy sector.

Among the objectives outlined in the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) strategy for Tunisia 2018-2023 are: “Supporting the competitiveness of Tunisian businesses by opening markets” and “Supporting Tunisia’s transition to a green economy”.

Specific goals were also targeted for achievement during the 2017-2022 period under Priority 3, including: “Developing a renewable energy program to support the private sector through consultation with the Ministry of Energy… and advocating for the banking model of PPAs (Power Purchase Agreements) with all stakeholders: the Prime Minister’s Office, the Ministry of Energy, the National Electricity and Gas Company, trade unions, and banks.” The document also emphasizes on “continuing to advocate for reforms with international financial institutions to strengthen private sector participation in key sectors (such as energy and infrastructure)” and affirms “agreeing with authorities on improving energy efficiency, including legal support for renewable energy.”

Tunisia is no exception to this pattern, as planning for renewable energy projects and their accompanying legal framework has been directly linked to the influence of European partners, especially Germany. As the fourth-largest industrial power globally, Germany is committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions and is a major player in the renewable energy sector, driving its pursuit of markets for its technology and expertise. Thus, it is noteworthy that the logo of the German Technical Cooperation Agency is prominently featured on almost all projects and studies related to the environment in Tunisia. Since the beginning of the Tunisian-German energy partnership in 2012, Germany has provided technical assistance to develop the energy sector in Tunisia in line with its strategic interests. Observers13 point out that the impact of this “support” is echoed in some measures of the 2015 law.

In September 2023, the Tunisian Ministry of Industry, Mines and Energy in collaboration with the German Agency for International Cooperation (GIZ), launched the National Strategy for the Development of Green Hydrogen and its Derivatives in Tunisia, with the goal of exporting more than 6 million tons of green hydrogen to Europe by 2050. Despite the widespread acclaim for this project, several negative aspects have not received sufficient discussion (and we will discuss explore them in the second part of this paper), as meeting the needs of the European Union and complying with its requirements may entail high environmental and social costs due to the consequences of these projects and their accompanying “reforms” on citizens’ rights to this vital facility14.

These insights shed light on the significant disparity in the speed of implementing government “commitments” between the energy sector (as a component) and the other components of the ecological transition strategy, as well as the National Strategy for Low-Emission and Climate-Resilient Development by 2050. While key sectors such as agriculture, health, and water (remaining components of these strategies) have largely stalled, the energy sector has rapidly accelerated, driven primarily by European lobbying efforts.

Projects with a primary focus on export

The TuNur solar project is one of the most prominent projects programmed in cooperation with the European side. This joint venture involves Nur Energy, a british-based solar energy development company, along with Maltese and Tunisian investors from the oil and gas sector, with the primary goal to exploit solar energy from the Tunisian desert to produce electricity.

The project is primarily located in Qibili and aims to generate concentrated solar power (CSP) and export it to Europe via undersea cables. According to the Mediterranean Solar Plan, the project aims to deliver 4.5 gigawatt-hours of electricity, with the primary export target being Italy, followed by France and Malta.

This project aligns with Europe’s broader strategy to enhance electrical interconnections with North Africa as an alternative to dependence on Russian gas.

This strategic direction was embodied in the revival of the Desertec program, a lobbying group founded in 2003 by the Trans-Mediterranean Renewable Energy Cooperation (TREC), an initiative stemming from the Club of Rome. The Desertec program’s mission is to develop electricity production from renewable energy sources in desert regions.15 As part of this initiative, three key consortia were established: the Desertec Industrial Initiative, a coalition of German industrial companies in the energy sector based in Munich, alongside MedGrid and MED-TSO.16

The Desertec project was abandoned in 2014 due to several factors, the most significant of which was Europe’s shift toward providing its needs of clean energy internally, due to the declining cost of solar panels at the time. Althoug, the announced reasons for abandoning the Desertec project in Tunisia included its high costs, the incompatibility of the national legal framework in Tunisia with the European vision for the project—especially regarding private sector involvement and energy subsidies—and the “lack of investor confidence”17.

The most prominent reason, however, was the disagreement between Desertec and Desertec Industrial Initiative.18 Despite this setback, the core philosophy of exploiting the Sahara Desert to fulfill European energy needs persisted and even regained momentum after the Russian war, reflecting Europe’s concerns about its energy dependency on Russia.

Subsequently, Tunisia significantly amended its energy policy measures through Law 12/2015, issued on May 11, 2015, which provides a legal framework for generating electricity from renewable energy sources. This law aims to define the legal regime governing the implementation of projects for producing electricity from renewable sources for self-consumption, meeting local demand, and exporting. It promotes private sector investment in renewable electricity production. This law was accompanied by a regulatory decree issued on August 24, 2016, which outlines conditions and procedures for executing projects that produce and sell electricity from renewable sources, including terms for purchasing excess power from independent producers.

The government revised numerous texts to encourage investment in renewable energies. I Besides projects for self-consumption (with the possibility of selling the surplus to the national electricity and gas company and transporting it via its grid), the 2019 law on Improving the Investment Climate introduced the ability to develop such projects on state-owned lands through licensing and on agricultural lands by entirely waiving the requirement to change their designated agricultural use.19

Tunisian Electricity and Gas Company: The cornerstone of the energy privatization process

Removal of direct and indirect subsidies of electricity

The Tunisian Electricity and Gas Company (STEG) is a pillar of the public sector, boasting an electrification rate of 98.8%, among the highest in Africa and comparable nations. This achievement is supported by the state through both direct and indirect subsidies, ensuring citizens have access to this crucial service without the burden of global energy price fluctuations.

Breaking the “dominance” of public companies over strategic sectors and eliminating direct subsidies on basic commodities and energy prices have long been among the most important “reforms” demanded by international financial institutions.

Under the influence of the 2013 agreement with the IMF, Tunisia embarked on reforms that included an audit, which resulted in the removal of preferential gas pricing from the Tunisian Petroleum Activities Corporation20. This compelled STEG to source from global markets, necessitating foreign currency loans from banks and subsequently increasing its debt levels.21

Despite the president’s sovereignty-focused rhetoric, the government persists with its reform agenda, focusing on the “gradual adjustment of electricity and gas prices to reflect actual costs” (essentially, the elimination of direct electricity subsidies) with the goal of phasing out direct electricity subsidies by 2026. This objective is outlined in both the 2023 Medium-Term Budget Framework document and the circular regarding the preparation of the 2025 state budget.

Renewable Energy: STEG Infrastructure in favor of Foreign Investors

Although STEG’s financial crisis is primarily a result of implementing reforms from international financial institutions, privatization continues to be promoted as a solution for energy provision, amid the company’s financial issues, even within the renewable energy sector. Law 12 of 2015 marks another step forward in this trajectory.

Within this liberal framework, STEG’s role in the renewable energy sector is confined to electricity transmission, purchasing surplus from self-generated sources, and issuing licenses for the establishment of production companies aimed at local consumption or export.

In other words, the public-private partnership revolves around leveraging the historical infrastructure of the public company for the benefit of the private sector, primarily foreign investors. This model transforms electricity into a commodity and transfers the true costs to citizens, as the foreign investor’s goal is profit, not providing a public service such as the National Electricity and Gas Company.22

In the same direction, international financial institutions continue to exert pressure on the Tunisian state to carry on with these reforms. For example, according to the strategy of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development in Tunisia (2018-2023)—one of the main financial arms for renewable energy projects in Tunisia—we find among the “necessary changes” the “STEG’s control over the energy sector (including renewables) and the excessive subsidization of energy.”23. Additionally, the bank sets as one of its goals “to support and finance the liberalization of sectors dominated by the state, such as renewable energies, to encourage private sector involvement.”

Recently, there has been a significant acceleration in the implementation of renewable energy projects and their legislative framework. This includes the government decree on the transmission of electricity from renewable sources, signed by Prime Minister Ahmed El Hashani six months after his inauguration (December 2023), and the memorandum of understanding on green hydrogen with Total in May 2024.

The decline of protest movements and the weakening of civil societies and political organizations, combined with the absence of public debate, have allowed the authorities to pass policies that impact national sovereignty —despite their rhetoric— and citizens’ rights to energy. This situation has also enabled international financial institutions to navigate around the “lack of social consensus and the potential tensions that could arise from structural reforms (like subsidy elimination),” especially in critical sectors such as energy, which the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development identifies as one of the risks and challenges to its projects in Tunisia.24

Green hydrogen

Following the establishment of the national strategy for green hydrogen production25 – funded by German cooperation – Tunisia has accelerated the implementation of planned green hydrogen projects in areas like Gabes.26 On the legislative front, a group of deputies introduced a bill 27 on April 30, 2024, to promote green hydrogen projects, which was subsequently referred to the Committee on Industry, Trade, Natural Resources, Energy, and Environment on May 9. This committee conducted a hearing with the initiative’s representatives on July 4.

Moreover, on Monday, May 27, 2024, Tunisia signed a memorandum of understanding with the French conglomerate Total Energies and the Austrian “Verbund” to develop and implement green hydrogen projects in Tunisia. According to this memorandum, Europe will receive green hydrogen, enabling it to achieve its goals of increasing the share of energy from clean sources, reducing dependence on Russian gas, while creating new markets for its investments, as European companies will gain from manufacturing and selling the necessary technology and expertise for these projects.

In return, Tunisia will provide essential natural resources for producing green hydrogen, such as water and land, at very low costs. However, Tunisia will also bear the environmental and social impacts of these projects, once again highlighting an unjust global distribution of labor and wealth.

Water draining projects in a drought-stricken country

Tunisia is grappling with a severe water crisis and is categorized among nations facing water scarcity. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in 2020, Tunisia’s per capita water allocation is approximately 390 cubic meters per year, substantially lower than the global water poverty line of 1000 cubic meters. In this context, the production of green hydrogen presents additional challenges, as it requires significant water quantities for the electrolysis process.

The production of one kilogram of green hydrogen typically requires between 10 to 15 liters of water. However, estimates suggest that up to 20 to 30 liters may be needed per kilogram, largely due to the inefficiencies of some hydrogen processing methods under natural conditions.28 Given the water scarcity in Tunisia, seawater desalination will be an alternative solution to meet the demands of green hydrogen production. Yet, this process carries negative environmental impacts. Desalination of seawater produces a highly concentrated saline byproduct that is discharged back into the sea, raising marine water salinity and negatively impacting marine life and ecological balance. Studies show that the disposal of this brine can increase salinity levels by up to 50% around desalination plants.29

Similarly, solar energy technologies also demand considerable water resources for cleaning solar panels and for the water-cooling processes necessary in desert climates. This represents a substantial threat to Tunisia’s water reserves.

Drawing parallels with Morocco’s experience, numerous prominent German firms involved in the Noor Ouarzazate Solar Complex advocated for CSP technology. Supported by the World Bank and the German Development Bank, this technology was chosen to serve the interests of German manufacturing companies despite its high-water demand. Notably, Morocco, like Tunisia, suffers from a “structural water crisis,” as characterized by the World Bank. An environmental impact assessment conducted before the project’s commencement estimated the expected annual water consumption at 6 million cubic meters, although actual consumption significantly exceeded this estimate. It is noteworthy that the Noor Ouarzazate Solar Complex has refused to disclose the true rates of its water usage.30

Real Estate Issue: The Risk of Land Grabbing

In a second phase of “developing” the legislative framework to facilitate renewable energy projects, amid escalating land-related issues, President Kais Saied employed decree powers to overcome obstacles to the exploitation of state and agricultural lands for these projects. Decree No. 68 of 2022, dated October 19, 2022, regulating “special provisions to improve the efficiency of implementing public and private projects,” exempted all renewable energy projects (not only those for self-consumption) from the requirement to change the agricultural status of lands, “if their feasibility is proven by the Technical Committee for Private Electricity Production from Renewable Energies.”31. This decree also revised the agricultural reform law, enabling foreign capital to utilize agricultural lands by merely establishing companies in Tunisia, without requiring Tunisian participation in their capital or management. It is noteworthy that this legislative change had previously failed several times in the Assembly of the Representatives of the People during the democratic transition.32

To expedite the Tunisian Solar Plan and meet the demands of international financial institutions, the Tunisian state seized disputed lands that had not yet been regularized, through five decrees issued after July 25, 2021.

These decrees awarded a French-Moroccan33 consortium approximately 400 hectares of communal lands in the Oulad Sidi Abid area. These lands are overseen by the Management Council according to the law according to the 1964 Law on communal Lands, amended in 2016, after previously being annexed to state property. Thus, the state took advantage of the lack of clarity regarding this type of land to make it available for foreign investors, exempting them from the regulations stipulated by the Agricultural Land Protection Law 34. there has been a recent increase in the pace of signing lease contracts for agricultural lands for renewable energy projects at low rates (e.g., 1200 dinars per hectare per year), driven by local authority pressures 35 in various regions including Chenini, Kebili, Gabes, etc.36

Conclusion: No “Just energy transition” without democracy

Although the prevailing discourse on “sustainable development” or “green economy” ostensibly advocates for energy alternatives that promise a fair transition, these terms are often hollow and do not reflect any genuine change in the prevailing extractive system.

The concept of a “Just Transition” posits that justice must be at the core of all climate solutions, ensuring that responses to the climate crisis address the structural aspects of the extractive energy model, while also considering class disparities, sovereignty, and democratic dimensions.37 It is, therefore, necessary not to consider the energy transition merely as a substitution of fossil energies with renewable energies – a pathway imposed by Western companies and governments – because, in this way, it remains nothing more than energy expansion, not energy transition.

It becomes clear, then, that what is referred to as energy transition, in the Tunisian context, does not include projects that diversify the energy sources needed by Tunisian society. Instead, it perpetuates the existing energy model while allocating Tunisian lands, water, and infrastructure for the benefit of foreign investors and for export purposes. Moreover, these projects are invariably linked to borrowing from international financial institutions, further increasing the country’s debt. The latest of these loans were three agreements ratified by the “Assembly of the Representatives of the People” to finance the ELMED project, aimed at establishing electrical interconnection between Tunisia and Italy and supporting the production of renewable energy.

This project’s funding was part of a memorandum of understanding signed by Kais Saied in July 2023 with the European Union38. The essence of this memorandum is to provide financial aid to Tunisia and overlook issues of rights and freedoms in exchange for the Tunisian state’s continued efforts to combat irregular migration and cooperate in the forced deportation of Tunisian migrants from the Schengen area or migrants intercepted at sea, and the implementation of European energy projects, echoing a situation reminiscent of the Ben Ali era.

Contrary to what is promoted, renewable energy projects do not involve technology transfer, and their operational capacity is limited. The countries that manufacture this technology and their economic fabric will be the beneficiaries of these projects in a way that sustains the global division of labor: Northern countries export high-value-added technology and industrial products, while Southern countries supply raw materials and cheap labor.

While Tunisia partially benefits from solar energy to meet its local needs, it gains little from green hydrogen, which is primarily aimed at export without substantial benefits to the Tunisian industrial sector. In addition, it requires the desalination of vast amounts of seawater, which could otherwise be used to address drought issues or for agriculture.

Moreover, the critical issue of water is overshadowing an equally grave but under-addressed real estate issue, where communal and agricultural lands are seized without regularizing their status, using various pressure tactics without considering the resultant social tensions.

The energy file once again reveals the falsehood of the current authority’s sovereignty rhetoric. The government invokes national sovereignty in response to civil society’s demands for respecting international obligations regarding rights and freedoms. Yet, it overtly conforms to European directives in matters that truly affect Tunisian sovereignty and vital resources, such as agricultural lands and water. This purported sovereignty 39 is further undermined in the migration issue, where Tunisia acts as a border guard for Italy, overlooking the responsibilities of its neighbors, Algeria and Libya, in the migrant crisis.

Finally, the authorities’ discomfort with this issue is evident in their handling of environmental protest movements. Activists from the “Stop Pollution” movement in Gabes faced harassment and pressure from supporters of the President of the Republic during their march to commemorate the decision to dismantle the chemical complex’s industrial units. They were accused of “agitating the situation to benefit opponents of the July 25 path.” by some social media pages supporting the president. Similar to the 18/18 movement in Jerjis, this scenario illustrates that no social movement, no matter how noble its cause, can be detached from fundamental freedoms, and that the populist authority, despite using the rhetoric and slogans of social movements, will not genuinely support them unless they align with its own agenda.

___________________________________________________________________________________________

- Newell and Phillips (2016): Neoliberal energy transitions in the South: Kenyan experiences, Geoforum, Volume 74, 2016, Pages 39-48. ↩︎

- Geels (2002): Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: a multi-level perspective and a case-study, Research Policy, Volume 31, Issues 8–9, Pages 1257-1274. ↩︎

- Geels (2011): The multi-level perspective on sustainability transitions: Responses to seven criticisms, Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions, Volume 1, Issue 1, 2011, Pages 24-40. ↩︎

- Spaces ↩︎

- Newell, P and Mulvaney, D. (2013): The political economy of the ‘just transition’ The Geographical Journal, 2013, doi: 10.1111/geoj.12008 ↩︎

- Bayliss, Kate & Fine, Ben. (2008). Privatization and Alternative Public Sector Reform in Sub-Saharan Africa: Delivering of Electricity and Water. ↩︎

- Friends of the Earth International, If it’s Not Feminist, it’s Not Just, 2021, https:// tinyurl.com/4j9dd8u9; Indigenous Environmental Network, Indigenous Principles of Just Transition, 2017 ↩︎

- Hamouchene, H., & Sandwell, K. (2023), Dismantling Green Colonialism Energy and Climate Justice in the Arab Region, Pluto Press, Transnational Institute. ↩︎

- Louati Imen – Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (November 2022): Tunisia, what is energetic in Tunisia? (Arabic) ↩︎

- Figures of the National Energy Observatory (ONE), cited in ITCEQ (2017): Politique énergétique en Tunisie, Notes et Analyses de l’ITCEQ, N°55-Mai 2017 ↩︎

- National Energy Observatory – ONE (December 2023): Energetic conjuncture ↩︎

- Louati Imen – Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (November 2022), art,cit. ↩︎

- OTE (2022), op. cit. p6 ↩︎

- Tunisian Observatory of Economy – Transnational Institute (2022): ‘Renewable’ Energies in Tunisia: An Unjust Transition, Briefing Paper No. 12 ↩︎

- Hamouchene, H., « Desertec: the renewable energy grab? », New Internationalist, 01 March 2015. ↩︎

- Tunisian Observatory of Economy (2015): ‘Desertec or Europe’s Plan B in Response to the Russian Threat,’ Analytical Notes ↩︎

- Louati Imen – Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (November 2022), art,cit. ↩︎

- Hamouchene, (2015), op. cit. ↩︎

- The Working Group for Energy Democracy – The Legal Agenda (March 19, 2024): In Southern Tunisia: Land Grabbing for the Benefit of Green Capitalism ↩︎

- A form of indirect energy subsidy ↩︎

- Tunisian Observatory of Economy: The Impact of IMF Reforms on the Public Electricity Service – Infographics (May 12, 2023) ↩︎

- Al Bawsala Organization (April 4, 2024) – Dialogue Meeting: Energy Transition and ‘Green’ Investments in Tunisia: Arbitrary Policies in Favor of Foreign Investors? – Intervention by Saber Ammar ↩︎

- European Bank for Reconstruction and Development: Tunisia Country Strategy as approved by the Board of Directors on 12 December 2018 ↩︎

- EBRD (2018), op,cit. ↩︎

- Ministry of Industry (06/09/2023): National Strategy for the Development of Green Hydrogen and its Derivatives in Tunisia ↩︎

- Express FM (June 26, 2024): Gabes: Providing the Suitable Ground for Green Hydrogen Projects ↩︎

- Proposed Law No. 2024/038 on Promoting Green Hydrogen Projects ↩︎

- Lampert, D. J., Cai, H., Wang, Z., Keisman, J., Wu, M., Han, J., Dunn, J., Sullivan, J. L., Elgowainy, A., & Wang, M. (2015). Development of a Life Cycle Inventory of Water Consumption Associated with the Production of Transportation Fuels. ↩︎

- Al Bawsala Organization (June 6, 2024) – Majalat Podcast: “Green Hydrogen Production in Tunisia: A Solution to the Energy Crisis or Clean Colonialism?” Guest of the Episode: Researcher and Activist in the Stop Pollution Campaign, Saber Ammar ↩︎

- Aïda Delpuech and Arianna Poletti – Inkyfada (November 11, 2022): TuNur: The Dark Areas Behind the Export of Tunisian Sunshine to Europe ↩︎

- The Working Group for Energy Democracy – The Legal Agenda (2024), art,cit. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- The deal awarded in June 2021 to the French-Moroccan consortium ENGIE-NAREVA for the implementation of a photovoltaic power station with a total capacity of 100 megawatts in the Sakdoud area, belonging to the Redeyef municipality in Gafsa governorate. ↩︎

- The Working Group for Energy Democracy – The Legal Agenda (2024), art,cit. ↩︎

- Al Bawsala Organization (April 4, 2024) – Dialogue Meeting, Mentioned. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Hamouchene, H., & Sandwell, K. (2023), op. cit, p11. ↩︎

- European Commission – Press Release: Memorandum of Understanding on a Strategic and Comprehensive Partnership between the European Union and Tunisia. Tunis, July 16, 2023 ↩︎

- The Legal Agenda – Tunisia (Issue 27: July-September 2023) ↩︎